Throughout June and July 2019, CrimethInc. operatives from South and North America visited fifteen cities in seven different Brazilian states to present the print edition of Da Democracia à Liberdade, the Portuguese version of our book From Democracy to Freedom. The tour also served as an opportunity to compare notes about resistance to the Trump regime and the far-right populist government of Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil. This report from our trip also offers an overview of the some of the social centers and organizing going on in Brazil today. We have been publishing reports and analysis of social struggles from Brazil for many years; you can read some of our articles here.

We participated in a total of 21 events, hosted by social centers, occupations, union headquarters, universities, autonomous research centers, and a few more unusual venues. The idea was to present the ideas in the book, but also to exchange experiences with those participating in social struggles in all the places we visited.

A video from one of the presentations in Porto Alegre, edited down to the English parts, summarizing anarchist resistance at the outset of the Trump administration.

Everywhere we went, we met people who were eager to discuss anarchist perspectives on democracy and exchange experiences of resisting capitalism and the far-right governments that hold power in the Americas and elsewhere around the world. It was also helpful that we brought hundreds of copies of the To Change Everything pamphlet in Portuguese, an accessible introduction to anarchist ideas.

We built new ties and strengthened longstanding relationships between movements, collectives, and social centers and occupations throughout the cities we visited. There are many differences between Brazil and the United States, but the differences that exist within each country are much greater than the differences between the countries. Borders and nationality are among the constructs that our rulers employ in hopes of preventing solidarity from emerging between the oppressed of all countries. For this reason, one of our chief objectives has always been to foster dialogue on an international basis.

The book From Democracy to Freedom was translated collectively. Digital and zine versions have been available in Portuguese since 2017. Now, thanks to the efforts of independent editorial collectives including No Gods No Masters, Subta, and Facção Fictícia, there is a high-quality print run of a thousand copies.

Here follows a short account of what we saw and learned on this tour, as a means to keep building these connections. Due to limited time and resources, it was only possible to visit three of the five major regions of Brazil. Next time, we aim to visit the North and Northeast regions of Brazil as well, in order to continue to broaden our exchange of experiences and solidarity.

Goiânia and Brasilia

Starting in São Paulo, we flew with our bags full of books and zines to the events in Goiânia and Brasilia. Lacking access to a vehicle for much of the trip, we depended on busses, planes, taxis, various metros, rideshares, and, of course, long treks on foot. All this, carrying hundreds of books and zines. We destroyed the wheels on several bags and carts along the way.

Our first stop was in Goiânia, at Casa Liberté, a social center that hosts activities organized by different collectives and anarchist movements in the region, such as the Autonomous Workers Federation (FAT). The event was organized in conjunction with the independent music label Two Beers or Not Two Beers Records.

Before the discussion, the organizers showed the documentary “Parque Oeste, Story of a Struggle for Housing in Goiânia,” which chronicles the illegal and lethally violent eviction of the Sonho Real occupation in 2005 and the victorious housing struggle of the families that survived. The police operation left 14,000 people homeless; they also executed at least two people in cold blood.

The event was attended by the film’s director and also by activist Eronildes Nascimento, a survivor of the eviction. Pedro Nascimento, Eronildes’s husband and the father of her son, was one of the people murdered by police during the eviction.

Over 100 people attended the event. We shared a panel with Eronildes, who expanded on the story told in the documentary and spoke about the struggles of the families who occupy a new area today known as Real Conquista, also in Goiânia.

Anarchists from all over Brazil participated in or supported the defense of the Sonho Real neighborhood. Brad Will, an anarchist and Indymedia journalist from the United States known to some of us personally, filmed the occupation and the eviction. His footage is included in the Parque Oeste documentary that was screened that night. Brad was murdered in Mexico in 2006 while filming the popular uprising in Oaxaca, one year after the eviction in Goiânia.

Eronildes knew Brad. She spoke about how his footage helped to corroborate reports about the violence of the state; without his courage, there would be considerably less evidence of what happened during the eviction. She told us that residents have had two plazas named for the two people known to have been murdered during the eviction, and are attempting to have another plaza named for Brad Will. We were deeply moved to learn this. We owe a lot to Brad for demonstrating that it is possible for activists from the United States to offer meaningful solidarity to people in much more targeted communities in the Global South and giving poor people in Brazil cause to trust anarchists from our circles.

Also, if we had not made our way to Goiânia, Brad’s friends in the United States might never have learned of this documentary made with his footage, or of the ways he is remembered in Brazil. It is poignant to imagine that there might have been a plaza in Goiânia named for a murdered US anarchist without news of this ever reaching his home. We will never know all of the ways that our efforts impact the world.

Today, Eronildes is one of the most important leaders in housing struggles in Goiânia. She explained that every day she is more inclined to anarchism because she has seen that it is only possible to obtain meaningful victories through grassroots organizing and struggle. She described how, in her experience, political representatives and parties always pursue their own interests.

Documentary trailer for Parque Oeste.

The next evening, in Brasilia, we held a lively discussion in an unusual venue: a video game arcade and bar. We met a lot of new people and exchanged materials and ideas about local struggles; we also discussed future publishing projects together. We had heard a lot about the buildings designed by communist architect Oscar Niemeyer for Brasilia, which was constructed as a planned city to become the capital of Brazil in 1960, but we didn’t have time to go downtown to see them on our tight schedule. The next morning, we flew back to São Paulo and took a bus the same evening to Maringá in the state of Paraná.

Maringá, Curitiba, Florianopolis, Criciúma

In Maringá, we spent the day with comrades in the city and got to know a little about its local history and spaces. We visited a delicious vegetarian and vegan establishment run by comrades, the Vaca Louca Café, where the doors of the restrooms are painted with the design from our classic gender poster, and walked past a venue where protesters gathered to oppose a Bolsonaro rally in early 2018. In the evening, we set up a table in front of the State University Student Directory, where many people were already waiting for the presentation and others gathered as they passed by.

The artwork from our gender poster on the restrooms at the Vaca Louca Café in Maringá.

A stencil at the university in Maringá.

In Curitiba, we spoke at another café, Veg Veg, which also had delicious vegan food and the artwork from our gender poster painted on their wall.

The artwork from our gender poster at the Vaca Louca Café in Curitiba.

In Florianópolis, we spoke on the campus of the Federal University of Santa Catarina at the Tarrafa Hacker Club, a community laboratory dedicated to disseminating skills in technology, digital security, science, and digital art. Despite several interesting political activities going on that night at USFC, dozens of people packed into the room, including many experienced activists. We had a lively discussion drawing on participants’ experiences in the Brazilian movements of 2013, indigenous organizing contexts, and experimenting with both democratic and autonomous decision-making models. Afterwards, we set up our literature table by a samba band performing for a large crowd in the center of campus.

The event in Criciúma was organized by Anarchists Against Racism at the Sociedade Recreativa União Operária club, a space run by seven collectives from the city’s Black liberation movements. The social center is the result of many people’s hard work to reclaim a longstanding community space, a Black community club founded in the 1930s. Since many people in Criciúma did not feel welcome in the predominantly white clubs at the time, they founded their own club for culture, recreation, socializing, and resistance. The massive building is set in a broad square with two grassy soccer fields in the middle of what is now considered a wealthy area. The participants are working hard to revitalize the space after years of abandonment. It was inspiring to exchange experiences of grassroots organizing and struggle with our hosts. We hope to do more to support their projects in the future.

Banners from Anarchists Against Racism at the Sociedade Recreativa União Operária club, a space run by Black liberation movements, in Criciúma.

Another banner at the Sociedade Recreativa União Operária club in Criciúma.

Porto Alegre

We took three days in Porto Alegre to offer both of the presentations we were doing on the tour and to learn about many of the projects that our comrades there maintain. On Saturday, June 29, we spoke about From Democracy to Freedom at the Humanities Research and Practice Association (Associação de Pesquisa e Práticas em Humanidades, APPH). We were excited to see another independent space dedicated to research and practical forms of anti-capitalist organizaing. APPH is a community space offering free or affordable workshops, lectures, and courses, dedicated to making the knowledge from universities and social movements accessible to all. Earlier in the morning, before our presentation, the philosopher Debora Danowski had spoken on climate change and the Anthropocene.

Tabling at the APPH in Porto Alegre. The poster says “When in Rome, do as the Vandals do.”

Artwork from Days of War, Nights of Love at Café Bonobo in Porto Alegre.

Artwork from Days of War, Nights of Love at Café Bonobo in Porto Alegre.

Artwork from Days of War, Nights of Love at Café Bonobo in Porto Alegre.

A Brazilian edition of Expect Resistance at Café Bonobo in Porto Alegre.

The next day, Sunday, we presented “Anarchist Resistance in the Trump Era” for the first time on the tour, at Café Bonobo, a vegan, anarchic, self-managed space. It was one of the most crowded events of the tour. In Porto Alegre, there are many cooperative initiatives such as this, at which people organize their labor, their schedules, and their plans without bosses or hierarchies. Another example is the Aurora space, which offers lunch without fixed prices—diners pay however much they choose to and take as much as they want from the tray of paçoca, the delicious peanut snack local to southern Brazil.

The Aurora Café in Porto Alegre.

Artwork at the Aurora Café, next to a flag of the MST, one of the world’s most powerful land occupation movements.

The ceiling of the Aurora Café in Porto Alegre.

Monday was the first day off on the tour. Our generous hosts loaned us their bikes to see the city. We visited the anarchist bookstore Taverna, returned to the aforementioned Aurora, and received a tour of the occupation Utopia e Luta one of the largest squatted residential buildings in the Americas. This amazing space in the city center includes 43 apartments, a huge roof garden, a screenprinting workshop, a capoeira studio, and many other resources. The visit took a long time and unfortunately we could not visit the Ateneu Libertário of the Gaucha Anarchist Federation. Next time!

The façade of the occupation Utopia e Luta in Porto Alegre.

The façade of the occupation Utopia e Luta in Porto Alegre.

The foyer of the occupation Utopia e Luta in Porto Alegre: “You are entering a territory of popular self-determination.”

Banners hanging in one of the common spaces of the occupation Utopia e Luta in Porto Alegre.

All of the stairwells are decorated with artwork like this in the occupation Utopia e Luta in Porto Alegre.

São Paulo, Peruíbe, Santos

In São Paulo, in addition to consuming liters of açai, going to the museum to see a painting by Hieronymus Bosch, and sneaking onto the university campus to see capybara, we spoke in many venues, including a room in the Copam building, the Casa Plana bookstore, and the Centro de Cultura Social (CCS). Active since 1933, the CCS is one of the oldest anarchist spaces in Brazil; it hosts an archive that goes back over a century, having survived the military dictatorship of 1964-1985. Looking through it’s holdings, we found a picture depicting the lantern of knowledge driving off the representatives of the Church, then found a photograph from the very beginning of the 20th century showing the picture hanging behind a group of anarchists from that era. It was heartening to be among objects that bear witness to the indomitable spirit of Brazilian anarchists across the decades.

A figurine representing the anarchist fighters in the Spanish Civil War at the longstanding Centro de Cultura Social (CCS) in São Paulo.

After the talk at CCS, we hurried to the Casa da Lagartixa Preta pizza party in Santo André. Run by the Activism ABC Collective, the Lagartixa Preta has been around for over 15 years; it is one of the major projects that materialized in a social center after the end of the anti-globalization movements of the early 2000s. During the pizza party, we heard a series of spoken word performances and looked through their archive of anarchist literature.

The “Wash Your Own Dishes” poster in Portuguese over the sink at the Casa da Lagartixa Preta in Santo André.

Having eaten our fill of delicious vegan pizza, we visited Semente Negra, the beautiful ecological space where the annual No Gods No Masters festival takes place, near the tiny town of Peruíbe. There, we restocked our bags with books and zines and attended the little town’s Festa Junina Fair. Our hosts also took us to visit their comrades at the Tapirema Village on recently reclaimed Tupi Guarani territory. This is one of 12 villages that have been reestablished on ancestral land at precisely the location where the colonization of so-called Brazil first began. Anarchists from the coast of São Paulo having been working in solidarity with the Guarani peoples as they reconstitute their traditional settlements and defend the forests and water from the latest capitalist and state assaults. For a few hours, we compared notes with them and saw the results of the inspiring work they have been doing.

The gate of Semente Negra, an ecological land project where the annual No Gods No Masters festival takes place, near the tiny town of Peruíbe.

A view of a pool at Semente Negra, an anarchist sustainable ecological project that organizes in solidarity with local indigenous groups.

Another part of the Semente Negra project, which extends across a broad area.

The last event in the state of São Paulo was in the town of Santos, at the Cinemateca de Santos, an autonomous space that maintains a huge collection of films and hosts movie clubs and discussions. The event was organized by anarchist comrades from the Carlo Aldegheri Library. A serendipitous moment occurred during the discussion, when one of the speakers drew an example from an assembly during the protests in Miami against the 2003 Ministerial regarding the proposed Free Trade Area of the Americas, at which a representative from the official labor unions had duplicitously attempted to persuade anarchists and other activists to cancel their protest completely. It turned out that one of the older Brazilians in the audience had also attended that same assembly in Miami, and also experienced this infuriating betrayal from the labor unions.

Divinópolis and Itaúna

In the small city of Divinópolis, we spoke at SINPRO, the headquarters of the state teachers’ union. The audience was comprised of an unusual mix of fierce union members and Stirnerist punks. We enjoyed an in-depth conversation about the relationship between democracy and racial issues in the Brazilian and US contexts. Some participants expressed the intention to deliver a copy of the book to each teachers’ union in the city and to the libraries of as many schools as possible.

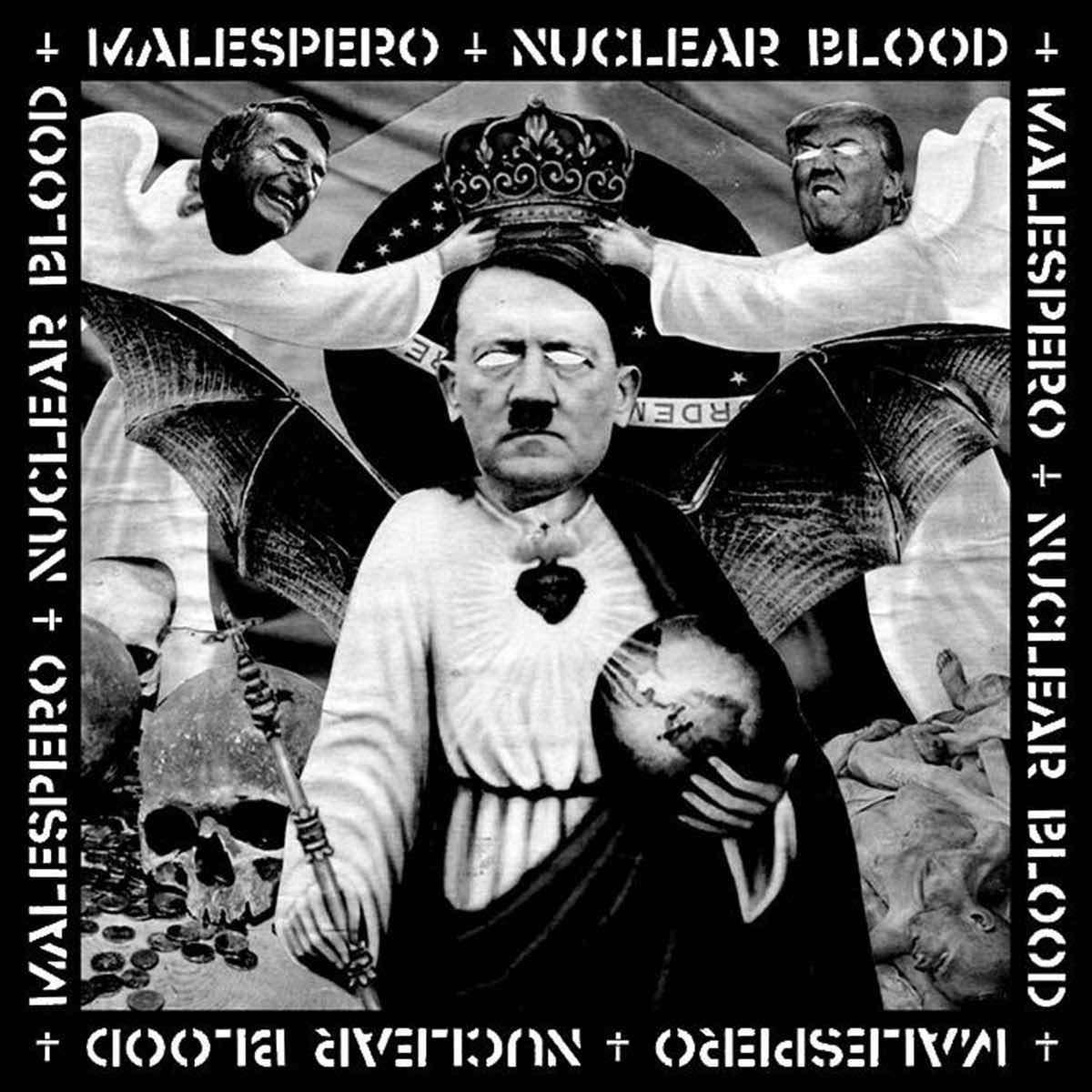

Cover of the album of the band Malespero, from Divinópolis, which summarizes one of the themes we discussed on the tour.

The next day, we spoke at a bar in Itaúna, like old-fashioned labor agitators, then hit the road early to Belo Horizonte.

Belo Horizonte

In Belo Horizonte, we spoke at two venues. The first was at the Federal University School of Architecture, where we joined in a panel alongside two participants in social movements and local politics. One of the speakers was a militant involved in the housing movements (Popular Brigades) and a councilwoman of the Muitas/PSOL platform, which, like other parties such as Podemos in Spain or Syriza in Greece, emerged from social movements and popular unrest and managed to get candidates from a long trajectory of grassroots social movements elected to legislative positions. Another person on the panel was a member of the Popular Unit, a newly formed socialist party that also focuses on militant housing struggles (MLB / PCR).

Each of the three participants presented their reflections on democracy based on the struggles and movements in which they participate. We spoke last, opening up a lively debate about the uses and limits of democratic discourse and electoral strategies. Unlike many cities in Brazil, during the June 2013 uprising Belo Horizonte saw various spectra of the left, anarchists, Trotskyists, Stalinists, socialists, and independent individuals all attend the Horizontal People’s Assembly (APH) and take the streets together, creating a common conviviality. This is why such a panel was possible at all.

For our part, we sought to identify the differences between principles and projects that seek to employ the state apparatus and those that refuse and delegitimize it. We want to see participants in our movements critically evaluate the costs of participating in institutional politics, as well as the apparent benefits. It seems that our colleagues, although they participate in political parties and exercise legislative mandates, agree—at least in theory—that the most effective and efficient way to promote social change is via self-organized direct action. Likewise, they were all quick to agree that democracy has failed to deliver on its promises. Yet they continue to legitimize the idea of government itself and to invest in strategies that take for granted that political power must be centralized in monolithic institutions. All around the world, we see that faith in democracy has eroded, but nothing else has taken its place. This leaves organizers struggling to squeeze diminishing returns out of discredited rhetoric and rituals, while authoritarians endeavor to fill the resulting vacuum. That is why we consider it so important to popularize a robust anarchist alternative to democratic discourse, emphasizing the importance of horizontality, decentralization, and solidarity.

The next day, on Friday, we spoke at Kasa Invisível about anarchist resistance to the Trump administration. In Belo Horizonte, like almost all major Brazilian cities, there are occupied neighborhoods and buildings in which hundreds or thousands of people live. However, Kasa Invisível is currently the foremost occupation in Belo Horizonte based on the framework of the international okupa/squatting movements. Composed of three houses located where the city center abuts one of the wealthiest areas, it is the longest occupation of its kind in the city. It serves as residential housing and as a cultural center open to the community, providing space for meetings, seminars, and events for collectives and social movements that do not have their own space. It remains an autonomous space, unconnected with parties or other institutions, operating according to the principles of horizontality, self-management, and opposition to capitalism.

Kasa Invisível in Belo Horizonte.

Kasa Invisível.

Paraty and Rio de Janeiro

Shortly after Friday’s presentation in Belo Horizonte, we caught a series of buses to reach the FLIPEI book fair in Paraty, just in time to participate in a panel early Saturday afternoon about insurrection in Brazil and the release of Chamada, a collection of calls and manifestos. That night, we participated in another panel about anarchist and anti-fascist resistance. We shared the latter panel with Acácio Augusto, an anarchist comrade and university professor from São Paulo State University, and with Mark Bray, who was in Brazil to see his book Antifa: The Anti-Fascist Handbook launched in Portuguese.

FLIPEI, the Literary Party of Independent Publishers, is organized by left and independent publishers; it takes place in Paraty at the same time as FLIP, a longstanding literary fair that is among the largest in the Americas. Dozens of debates and lectures occur at FLIPEI, with the speakers presenting from atop a pirate boat docked in the port. The first floor of the boat functions as a bookstore offering a wide range of publications. Big names from social movements, intellectuals, and all sorts of activists, left-wing activists, and anarchists attended the five days of the meeting. Unfortunately, due to our demanding schedule, we were only able to be there on Saturday.

The FLIPEI by day in Paraty.

The boat from which the speakers present at the FLIPEI by night.

The audience listening from the shore at FLIPEI by night.

At night, the scene was enchanting. The crowd listened from on dry land while we swayed in the river, just 500 meters from where it meets the sea. After so many airplanes, buses, trains, cars, and bicycles, all that remained was for us to catch a boat to complete our tour of different modes of travel in Brazil.

On Sunday, we hurried to the city of Rio de Janeiro for the penultimate event of the tour: a full evening of presentations at the Fosso space in Santa Tereza. The neighborhood looks out over the city, between Morro dos Prazeres and Fallet. The view is breathtaking—the metropolis spread out before us like a toy set. Sometimes we saw tiny monkeys hopping from tree to tree in front of us. From the balcony, we could hear all the sounds of the various neighborhoods of Rio below: raucous socializing, live music, car engines, dogs barking, and—occasionally—gunfire.

The view of Rio de Janeiro from the balcony of at the Fosso space in Santa Tereza.

Our last activity was scheduled for Tuesday, July 16: a discussion at Morro da Providência, the oldest favela in Rio de Janeiro, in the heart of downtown. Our hosts were the Organização Anarquista Terra e Liberdade (OATL) and the Rede de Informações Anarquistas (RIA). The presentation took place in front of the location of the Pré-Vestibular Comunitário Machado de Assis, where since 2009 anarchists have offered the community a popular preparatory course to equip young people from Providência and the surrounding areas to take college entrance exams.

The first speaker was a former student in the program, who is graduating from college today and is now a teacher in the project. The discussion that followed was one of the liveliest of the tour. It felt good to end the tour in the company of all the students, teachers, and activists from various groups who attended, hosted by a lasting and important project. Several younger people spoke eloquently about different forms of resistance, about the mechanisms of repression in Brazil and specifically in the favelas, about organization and social movements, drawing parallels between the conditions of the oppressed and Black populations and the forms of struggle in the United States and Brazil.

As we said, what unites us in our struggle against oppression is far greater than the borders, language, and contextual differences that might separate us.

Final Thoughts

We would like to thank everyone who helped to make this tour possible, whether by organizing events, helping us to spread the books, posters, and zines we brought, or sharing ideas, food, mattresses, and space with us. We are also grateful for all the publications and other materials we obtained on this trip. This support network is what makes it possible for us to cross countries and continents and to establish lasting connections between anarchist and anti-capitalist movements and social centers.

Our struggle for freedom depends on us building bonds, solidarity, and dialogue, breaking down every fence and border that could divide us.

Até a próxima! See you in the fight!

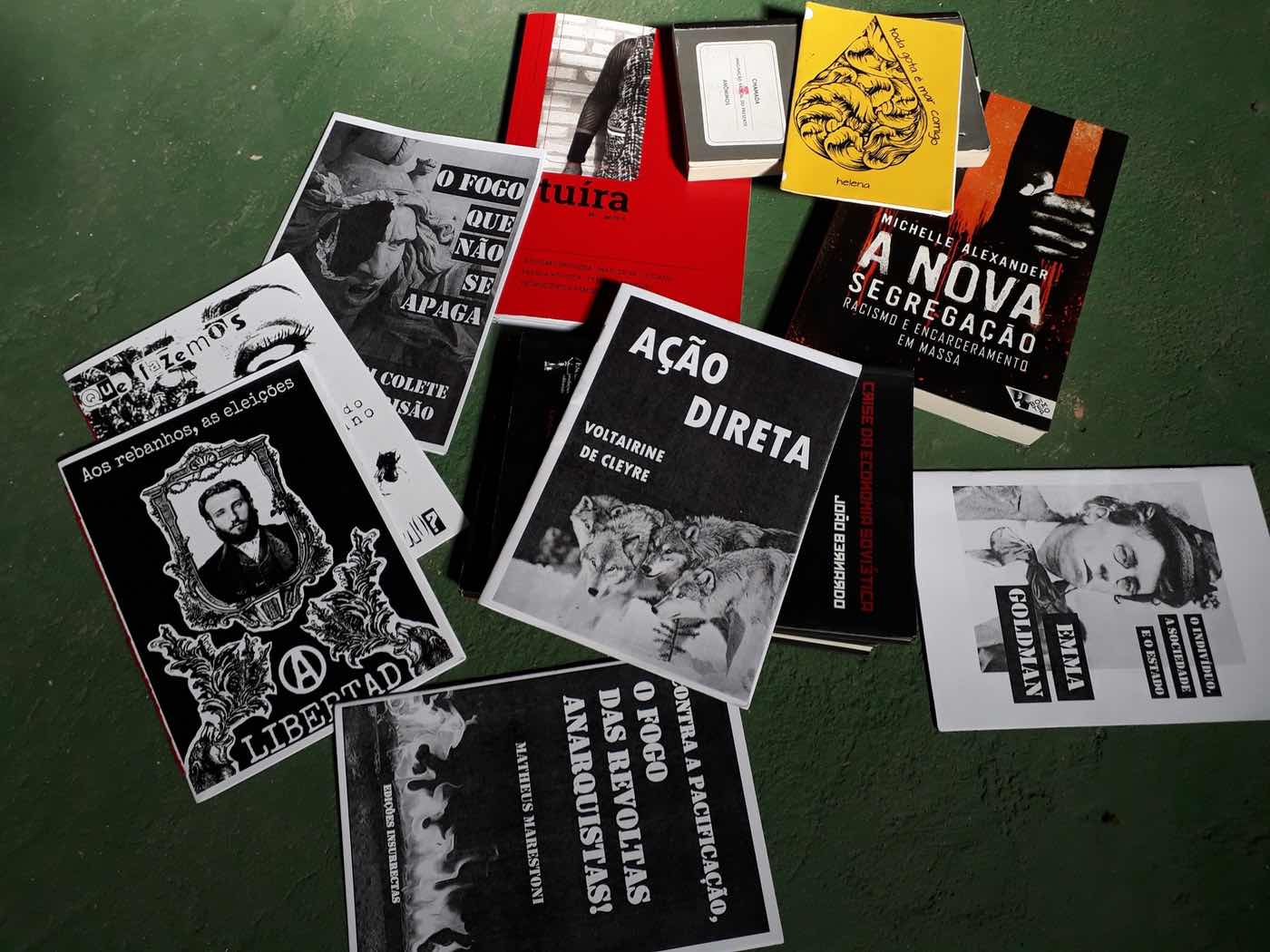

Some of the books, zines, posters, and CDs we acquired in the course of our trip.

More books and zines we acquired in the course of our trip.

Still more of our acquisitions.

Appendix: Street Art in Brazil

Compared to the United States, the streets of Brazil are filled with unpermitted expression, from the intentionally anti-aesthetic pixação scrawls to breathtaking compositions the span of a full city block. Here are just a couple examples that caught our attention.

Wall art Casa Liberté in Goiânia.

We for ourselves.

Vandal love.

Capitalism will destroy itself—but first, it will make you destroy yourself for it.

A cryptic poster at the Federal University of Santa Catarina in Florianópolis.

Anarchist artwork in one of the venues we visited.

Street art in Belo Horizonte.

Anti-fascist graffiti in Rio de Janeiro.

Classic anarchist graffiti in Rio de Janeiro from the movements of half a decade ago, which still remains today.