A secret children’s book passed from hand to hand, invisible to the market. After a decade and a half, we’re finally offering a zine version of The Secret World of Duvbo, the companion to our other children’s book, The Secret World of Terijian. This is a story about the furtive outlets we create for the parts of ourselves that do not fit into our ordinary lives—about the potential for transformation hidden within seemingly staid and conservative communities—about how the courage of one can become the courage of all.

Click the image to download the PDF.

This story has followed a long and winding path to reach your hands. The plot line was conceived in São Paulo, Brazil in early 2000. The first draft was composed at the end of January 2002, at Demonbox, a now-defunct collective house in Stockholm that, incidentally, was also the original European publisher of Days of Love, Nights of War. It was written as a gift for Arwin, who was born the following May in the real-life neighborhood of Duvbo.

In 2004, after publishing several books for sale on the market, we wanted to make a book that would only be available through gift economics. We printed a few thousand copies of The Secret World of Duvbo and gave them away to friends, lovers, and charming strangers over the following years.

Traveling in Minnesota in 2006, we discovered a new CrimethInc. cell that had composed a sequel, The Secret World of Terijian. In 2007, we published it in the same format as The Secret World of Duvbo, selling it as a fundraiser for defendants accused of earth and animal liberation. Within two years, the authors were themselves imprisoned on such charges and we had to raise funds for them as well. By then, most of the print run of The Secret World of Duvbo was long gone.

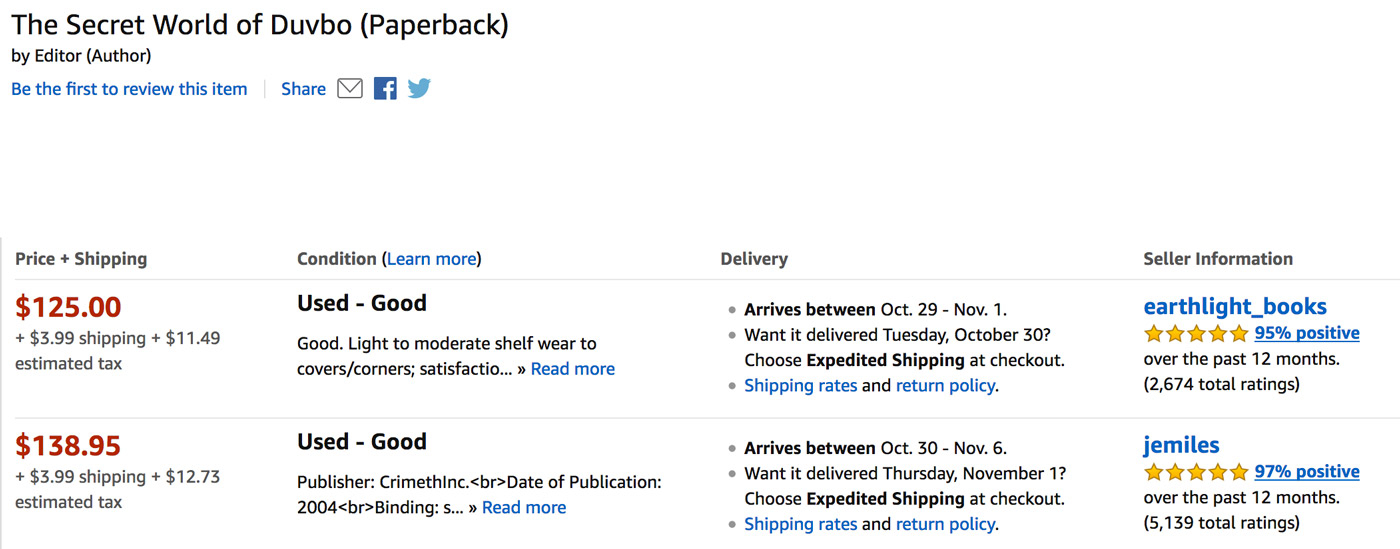

In 2018, we saw copies of the 2004 printing of The Secret World of Duvbo selling online for $125 and up, shipping and tax not included. We had eluded both the market and the internet for 14 years, but they were finally catching up to us. We prepared this edition to make sure that the text can still reach you outside the exchange economy, if no longer in the context of personal interaction that gave the original printing its special power. May we meet someday as friends, nonetheless.

Burn every toy store and replace them with playgrounds,

-CrimethInc. Children’s Crusade

The Secret World of Duvbo

A magical story about a perfectly ordinary world

for Arwin

Little One,

I wanted to write the most perfect story for you, so you would know how excited we all are for you to join us. I went around with a blank notebook for weeks, trying to work out the perfect first line for a perfect story. Finally, since I couldn’t come up with it, I moved on to trying to work out the perfect second line. I went through every line that way, right up to the last one, without any success. And then it hit me: I had written a perfect story, after all, but since this is not a perfect world, the story couldn’t join me here—it was waiting in another universe, the one where everything is perfect, even me.

To solve this problem, I had to sit down and write you an imperfect story, so at least you would have something to read. If nothing else, I think I’ve succeeded in doing that. By the time this reaches you, it will have been waiting for years; but all the same, late as it is to say this—welcome here!

Yours, ——

I.

Duvbo was a sleepy town in the world that is just like our world in every respect except that it is the one in which stories like this one take place. It wasn’t particularly close to or far from any other towns, and although people came in and out sometimes, life in Duvbo centered around what was going on in Duvbo, which generally wasn’t much at all. The residents didn’t seem to think much about this, but if someone had asked them, they probably would have answered that this was the way they preferred it.

If you were to take a walk around Duvbo on a sunny afternoon, you would pass through neighborhoods of modest houses, a few to a street, trees shading the well-trimmed grass behind white picket fences. Whatever path you took, you would be bound to come eventually to the center of town, where there were a street of shops, a street of civic buildings, and a central square where they intersected. It was a large enough town that a small child could get lost in it, but not so large that he would not quickly be found and returned home.

In this town there lived one mayor, four policemen, six firefighters, three mail carriers, four hundred and twelve assorted other workers, some retired, and their one hundred and nineteen children, most of whom attended the one school, which was staffed by nine teachers, including a particular Ms. Darroway, who taught mathematics. In addition to all these inhabitants, there were two especially grumpy retired army officers, who don’t come into the story until later, and one especially shy, especially sensitive boy, Titus, who will be the hero of this tale.

All in all, then, there were five hundred and fifty seven residents of Duvbo; you should try to remember this number, in case it becomes important later on.

Let’s start with Titus: he was a tousle-headed little fellow, perhaps a little shorter than his classmates, given to daydreaming and distraction but no more preoccupied than any other child his age. He wasn’t a boy to stand out in a crowd, but on closer inspection you might notice him—he would be the one near the edge of the group, looking one direction while everyone else was looking the other. Truth be told, he paid more attention to his surroundings than adults gave him credit for, and sometimes noticed things no one else did.

The mayor was a great big ostentatious man given to flaunting extravagantly ordinary ties and delivering long-winded speeches about nothing in particular, and Titus only saw him on special occasions like the county fair or the Christmas parade at the end of autumn. He didn’t see too much of the police officers, either, and though police officers in other towns are known for doing quite horrid things, these four weren’t really a bad sort. The firefighters would come to his school once a year to ramble through a presentation about fire safety and prevention, but as far as Titus could tell, there were never any fires in Duvbo for them to put out.

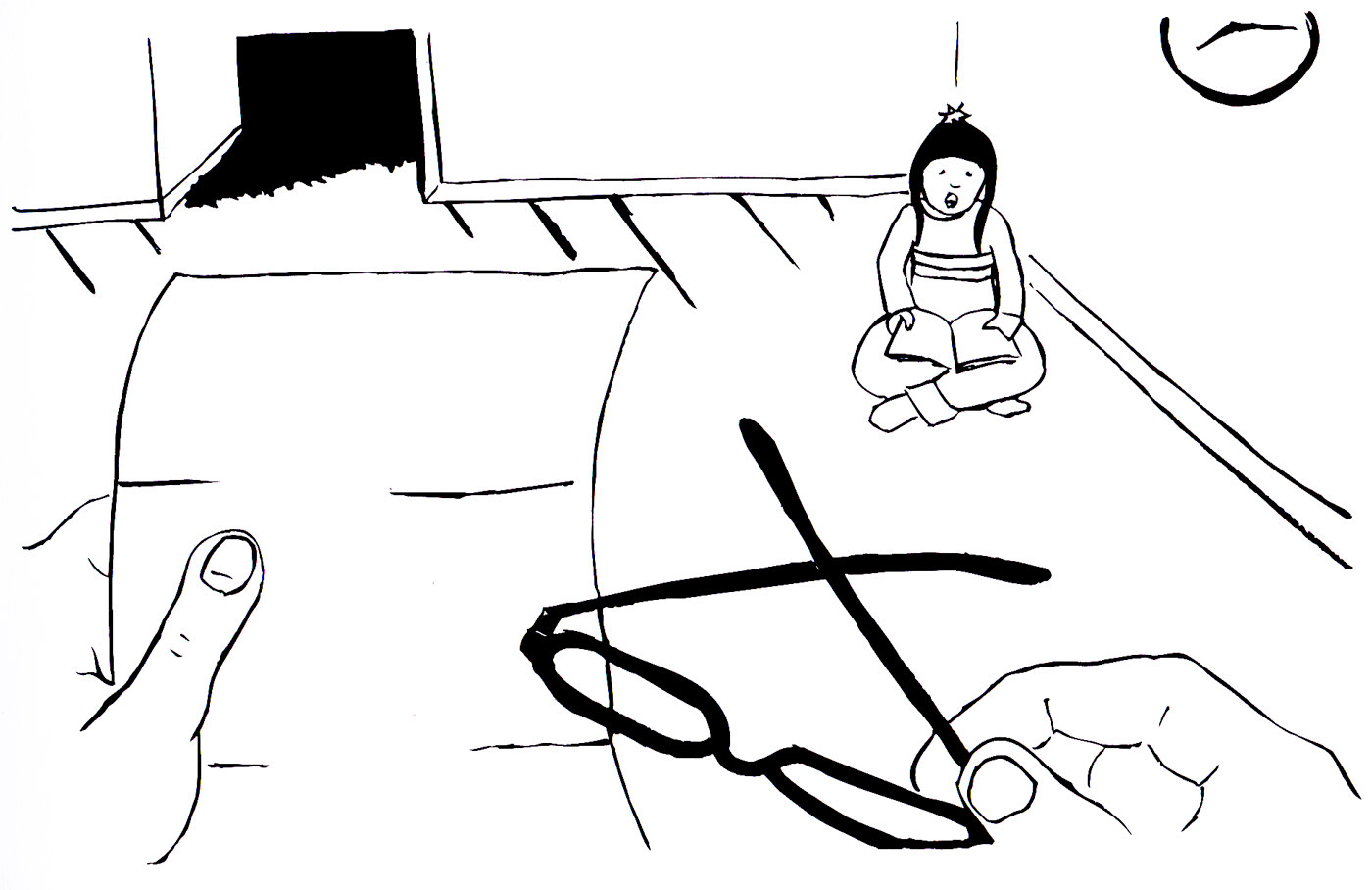

The mail carriers were more interesting to the boy, or at least one of them was. Every day on his way back from school, Titus would pass her coming down the driveway from his house, having just dropped the mail in the mail slot; as soon as he had passed her, so she wouldn’t see him do it, he would run up the front steps and fling open the door to see what had arrived. Nothing ever had, of course, except for bills and other confusing, humdrum things that set his parents to muttering; but all the same, it seemed to Titus that a mail carrier ought to bring important packages, magical invitations, parcels that would open to reveal hidden entrances to other worlds or at least maps to buried treasure. So every afternoon, just in case, he was there, fingers crossed, to check the mail—and every afternoon it was the same: bills and advertisements.

As you’ve probably already guessed, Ms. Darroway was Titus’s mathematics teacher, and he sat in her classes many long hours every week daydreaming and counting down the minutes until he and the mail would arrive on that doorstep. She was a stern, strict, unlaughing woman, and would always catch him with his head in the clouds and chastise him in front of his classmates. Still, his mind would wander, and he couldn’t help following it out those windows, across the placid fields around Duvbo, over the hills and far away into wild jungles where women and men with painted skin rode winged fish up black rivers to abandoned cities at the feet of towering mountains… sometimes when the bell rang to release him, he was almost sorry to come back to his seat, even though he knew it was time to run home to see if the package he longed for had finally arrived.

Through the course of this tale, you may sometimes wonder where Titus’s parents were; the answer is, of course, that they were there, somewhere in the background, like many people’s parents are these days. Titus was not so lucky as to have parents who knew how lucky they were to share their lives with him, and he had to work a lot of things out on his own. This is the story of how he did, and of how much of a difference it made for everyone.

Weeks and weeks of hopeful afternoons added up to months with still nothing special in the mailbox. At Titus’s young age, that seemed like an impossibly long time for nothing special to happen, and he began to fear that something was wrong in the world; but everyone around him carried on in such a nonchalant manner, and with so little visible desire for Something Special to arrive in the mail or from any other direction, that some days he wondered if something was simply wrong in himself that he should want such a thing. If he had been a braver boy, he thought to himself in a tone of accusation, he would have asked the mailwoman if strange packages from exotic lands didn’t show up on at least some doorsteps, sometimes; but he was at that age when boys become too self-conscious to ask such things aloud, even if a part of them still shouts the question silently.

He should not have been so quick to criticize himself, for as it would turn out, he would demonstrate great bravery and initiative when the time came. But he had no way of knowing this, yet, and went about thinking of himself as something of a coward, hoping for an opportunity to prove his courage with the same mounting impatience with which he awaited the arrival of something magical in the post.

This impatience led him to do something that parents tell their children Never To Do Under Any Circumstances, the sort of thing they certainly do not want little boys doing in the stories their children read—so if you’ve gotten this far, you can consider yourself lucky. Fed up with a life in which nothing ever happened, Titus began secretly staying awake until everyone else in the house was asleep, and then—this is the really controversial part—sneaking out of the house to take walks in the witching hour of the night. Each night he would wait until he heard the low rumble of his father’s snoring, then the quieter whistle of air between his sleeping mother’s lips, and, after counting breathlessly to one hundred, would hold the pillow over the window latch to muffle the sound as he unlocked it. Then he would open the window just wide enough to slip his body out, and lower himself carefully to the ground a few feet below, trembling as he did in the thrill of doing something so frightening and forbidden. Some nights he would step on a twig as he reached the ground, and freeze in terror for minutes until he was sure he hadn’t awakened his parents; he began to check the area under his window for sticks in the afternoon, after the latest disappointing batch of bills had arrived.

On the first few outings, he didn’t stray far from the house—it was enough just to stand in the dim streetlight in the front yard, looking at the dark forms of trees that loomed overhead and savoring the chill air on his face. After a week of this, though, he had built up enough courage for a short expedition down the street, and then another. The whole world looked so different at night—everything that was familiar in daylight became, in the still starlight and emptiness of sleeping Duvbo, spooky and nearly magical. Squinting at the silhouettes of street signs made blank by the blackness, almost swallowed up by the silence in which his footsteps boomed, Titus felt like the last human being on earth—or the first.

Parents and other adults forget this as the years pass, but you know it well, I’m sure: children’s lives are electrified by secret adventures like this, given their true form and meaning by moments no one else witnesses. Already Titus was daydreaming less about the afternoon mail and more about what he would do later in the evening while the city slept; and every day in class a taciturn, tired Ms. Darroway would snap him out of his reveries with a sharp word or a rap on the wrist.

One night, flushed with a growing confidence from weeks of these expeditions, Titus crossed a line. This evening, when he arrived at the edge of the neighborhood he knew, he didn’t turn back, but paused—and then, mustering all of his little boy’s bravado, walked forward, onto a street he could not recognize in the darkness. Every step was a terror, at first: he laid his feet down as if the pavement might give way beneath them, or the whole town suddenly be transformed into thick and impassable jungle. As successive steps revealed these fears to be unfounded, he shook himself, tried to relax a little, and returned to his usual pace. It was a little like walking with your eyes closed, which, if you’ve never done it, you should try some time: he expected to hit disaster at any moment, and shuddered sometimes despite himself, but the disaster did not come, and if he didn’t think about it too hard, it was as easy as anything to keep moving.

Soon, he began to feel free and sure of himself in a way he hadn’t before in the few long years of his young life. Here he was, out in a fairyland no one else ever saw, navigating it with the fearlessness and finesse of a true explorer; if those sleeping civilians only knew! He rounded corners and set off down new lanes like a pirate captain swaggering onto the beach of a newly discovered island. Finally, he decided it was time to return to his bed.

And then, with a dread that ran as deep as his elation had soared high, he realized he was lost. He hadn’t kept track of every turn as he should have—and in the dim of the streetlamps, all the landmarks he had haphazardly picked out looked the same. He took one familiar-looking road, but it led to no others he remembered; he turned back, and tried another, only to have second thoughts—and, upon trying to retrace his steps, lost track of his path altogether.

Looking on from above, as it were, we can see that Titus had not strayed more than a few streets from his neighborhood; but from where he stood, in the murk of moonless night, it seemed home might as well be a thousand miles away. He wanted to sit down and cry, but he knew he was in such deep trouble that he couldn’t afford to waste a moment. Bravely, he walked on, deeper and deeper into the maze of his own confusion, hoping now against hope that he might stumble upon something he recognized—Duvbo was not such a big town, after all. Still, nothing of the sort appeared, for what seemed like hours and hours and miles and miles, and he was in the final stages of panic when he was startled by something altogether extraordinary and unexpected.

At the far end of the street he was passing on his left, he made out a glimmering distinctly different from the light the sparsely scattered streetlamps cast. It glowed, red and golden, and flickered as if with movement, or shadows. This was such a wild development that for a moment little Titus forgot all about his predicament: he had to see what it was, whatever the consequences. A lifetime of private fantasy had prepared him for this moment, and although his imagination conjured nightmares and well as wonders out of the light ahead of him, he turned and crept up the sidewalk towards it all the same.

As he proceeded, the street grew wider, and he saw that there was an open space ahead of him, in which he could make out the silhouettes of trees above and the texture of grass below. He also made out something else: figures, spinning and whirling around a great fire. The fierce light stretched their forms and magnified their proportions, made them appear unreal and enormous. This was beyond out of the ordinary—it was positively beyond belief, and Titus whirled internally at the shock and wonder of seeing with his own eyes, in monotonous Duvbo, a scene the like of which he had only dimly imagined in his mind. He froze, dizzy, torn between running forward and running away—but it was a choice he did not have to make.

In the very next instant, the great bonfire went out with a whoosh of sparks, and the figures disappeared in all directions, melting into the darkness. Titus leaped into the bushes behind him, but it was unnecessary—nothing and no one reappeared, and soon the stillness settled back in and resumed its air of permanence. Something else happened, too: Titus discerned the first glimmers of pink in the sky overhead—the sun was preparing to rise.

As it got lighter, the street came into focus, and Titus suddenly realized where he was: this was the central square of Duvbo! He could make his way home from here, if he followed the street past the fire station. There was no sign anywhere of the fire or the feral dancers, and he crept carefully out of his hiding place and across the cool grass, morning dew dampening his shoes, to start back.

He hurried through neighborhoods that once again took on an entirely different character, the rosy first light falling on familiar roofs and hedges as the dreams of slumbering families drew to a close. He was drained and out of breath, yet still shaking with adrenaline and awe from his discovery, when he slipped back in through his bedroom window and pulled it shut behind him, almost too distracted to muffle the latch. A few minutes later, as he lay in bed, heart racing, attempting to feign sleep, his mother came in to rouse him for school. It was as amazing to him as everything else had been that night that she didn’t notice anything unusual.

Titus spent the next day in a confused combination of exhaustion and exhilaration. It was impossible to think about anything but what he had seen, what it could have been, what he should do the coming night, and at the same time his brain was so foggy, his eyelids so heavy, his body so worn out that it was all he could do to stay awake in class. Ms. Darroway seemed particularly short-tempered and weary herself, and gave him no quarter whenever his head drooped to one side. Poor Titus pinched himself and kicked his feet against each other, trying to keep up at least a veneer of attentiveness, but with his mind swirling with dervish dancers and sleep deprivation it did little good. Finally, after five hundred years of mathematics and dour reprimands crammed into fifty-five minutes, class was over.

There was nothing special in the mail, of course, so Titus set himself to the task of killing the hours until his parents were asleep. What was it he had witnessed, after all, he wondered? Did witches visit Duvbo? Was it haunted by ghosts? Had he almost interrupted a gathering of bandits? Were there even bandits, or witches, or ghosts anywhere, anymore, in this age? The one conclusion he came to again and again was that, whatever the danger and however great his fears, he had to go investigate further that night.

But when the moment came, and his mother switched off the light in his room, he plunged instantly into sleep—long before his parents even retired to their room. He was simply too exhausted to stay awake any longer.

The next evening, of course, he was wide awake and electrified with anticipation. After he heard the first whistle of his sleeping mother’s breath he was barely able to restrain himself while he counted, as fast as possible, to one hundred. On the final number he bolted upright and threw open the window latch with scarcely any muffling at all, and hopped down to the ground, which he had carefully picked clear of twigs that afternoon.

Once on the street outside, apprehension set back in. What would happen if they caught him, whoever or whatever they were? What if they were unfriendly? They were certainly otherworldly, at least of another world than Duvbo. He couldn’t know what to expect from them, couldn’t begin to imagine. But there was no way around it: he would have to be careful, and find out what he could. He wrapped his scarf over his mouth and nose as an impromptu mask, more as a charm against his own fears than anything else, and set out.

He had carefully charted the route from his house to the central square that afternoon, so there was no chance he would get lost again; all the same, it was a very different walk in the darkness. The uncertainty of what awaited him ahead coupled with the gloom of the streets around him made the trek fearsome indeed. Had he been older and more what adults call “mature,” he might have reasoned himself out of it, or at least waited to return with reporters and a camera crew; but he was young, and innocently impetuous, and ready for magic.

And it was waiting for him. Drawing close to the central square again, he once more made out a light in the center, beneath the trees. It was less bright, and flickered less wildly; soon he saw that the figures around it were not dancing, now, but gathered in a great circle of seated silhouettes. In the middle, before the bonfire, one towering figure stood, moving its arms in powerful sweeping gestures. All backs were to him, so Titus moved in closer.

The standing figure was draped in a complete bearskin, the fur hanging in strips around the arms, the shadow of the open jaws obscuring the face within. And she was speaking: when Titus heard her words, he recognized it as a woman’s voice, one that sounded almost familiar, and yet at the same time was unlike anything he had heard before. Her tone was so clear and strong that it carried through the square and resonated in his chest, but it had a softness and a warmth that only deepened his impression of its strength. It was a story she was telling, a story like the ones he made up in mathematics class, but fleshed out with even more imaginative details and fantastic settings than his own: men tattooed maps to mysterious portals on their children’s skin, women traveled on subterranean streams to the inner space at the core of the earth, flew there in the zero gravity to a hidden moon floating within. He listened, entranced, and crept closer, despite himself.

The speaker concluded her tale with a line of eerie poetry, and then turned sharply in Titus’s direction: “And now,” she pronounced, “it is time for us to hear a story from our new guest.”

Titus jerked to his feet and stumbled backward, but before he could get any farther a pair of hands seized him from either side and bore him to the center of the circle. Little Titus stood there before the great fire, surrounded by dark forms in outlandish costumes, and froze like an animal under a searchlight. Impulsively, he tightened the scarf around his face, but there was no getting around it: he was caught. “Go on,” another figure urged him, in a tone of voice he could not decipher: “a story.”

Titus opened his mouth, and began to speak: haltingly at first, but then, discovering a voice of his own that he had never had cause to engage, he told, with mounting confidence, one of his own stories from his daydreams. He narrated for dear life, adding clever digressions and extravagant descriptions, hoping the shadowy circle would not be disappointed and have him flayed or burned alive.

At the end of his story, there was a silence. He looked, fearful, around the circle, but could not see the eyes of the ones watching him, could not imagine what would happen next—and then, all at once, there erupted from all hands a great applauding, and from all throats a great cheering, and in the next instant, as had happened two nights before, the fire went out in an explosion of sparks and all the figures disappeared abruptly into the darkness.

The following day Titus was as exhausted as he had been two days earlier, and as perplexed and excited. He sat in mathematics class, eyes pointed at the blackboard but unfocused, and reflected on his discovery. He had uncovered a fabulous mystery, a secret side of Duvbo that no one knew of but himself; it was amazing that such an exotic company would gather in the heart of such an ordinary, even dreary, place. Where were they coming from? What drew them here? He had the strange feeling that the pieces of the puzzle were right in front of him, but he couldn’t put it together. He resolved, head blurry with fatigue, to let himself catch up on rest that night, so he could be in top condition to investigate further the following evening. At that moment, Ms. Darroway wrenched him from his reverie with a sharp word. She looked as tired as he felt.

The night after, he was there again, making his way into the main square in the middle of the night, scarf around his face and heart pounding in his chest. Again it was different: now there was no central fire, but the area was lit by torches on the trees; some of the figures were playing instruments, sweet-voiced silver wind instruments and belligerent booming box-drums and great strange stringed things stroked with two-pronged bows, while the others spun and twirled and leaped in trailing scarlet gowns and elaborately layered veils and elegant black capes. It was a masked ball.

Still apprehensive, Titus paused at the edge of the torchlight, but one of the dancers saw him and, as she passed by, seized his hand and pulled him into the dance. He had never danced like this before; growing up in Duvbo, he had hardly ever danced at all. Now they were all clasped in concentric circles. They sped above the ground, feet barely brushing it, clutching each others’ hands lest they hurtle out into space, momentum pulling the circles ever wider as they spun faster and faster. In the center of the action, Titus now made out the imposing woman from his previous visit: the bearskin was gone, replaced by a wrap of dozens of multicolored scarves, but it was unmistakably her. She held hands with no one, but stamped out her own dance, kicking her legs high over every head and swinging her arms like the wings of a fierce bird of prey; the scarves retraced her movements in the air behind her in slow motion, following like a shadow dancer in her footsteps.

All in an instant, the dance shifted, and each participant took a partner. Titus was chosen by a young woman with a brightly painted face, who lifted him up high in the air above her; then the music paused for an instant, and the partners switched. Now Titus was passed to an impossibly tall, long-legged man—no, he must be wearing stilts!—and now, at another sudden pause, to a pair in matching costumes, and then to another partner, and another. The song grew rowdier, faster, more forceful and irresistible; it seemed to be emanating from his own pounding heart.

Suddenly, Titus was arm in arm with the woman in the scarves. The rest of the world seemed the fall away to a great distance, and even the deafening music became remote, manifesting itself instead as the inexorable rhythm of their bodies. She was clearly possessed of a superhuman strength, and as her companion, it was communicated to him: Titus found he could leap high in the air, spin in circles, lose himself in movement in a way he never had before. The musicians struck a high, drawn-out note which brought the world back into focus for a second as he spun to face his partner, and then again cut all the sound for a second’s pause: and in that instant, looking into her eyes, he recognized exactly who this woman was—it was Ms. Darroway.

Another dancer seized him, and she disappeared behind him into the throng before he could react. Now, looking around, he saw others he could recognize in the torchlight, despite their disguises: there atop the stilts was the fireman who did the yearly fire safety presentations, and there behind a veil was an older student from the school, and there—that was even the woman who brought the mail to his doorstep every afternoon! This was far stranger than any strangers’ carnival could have been. And once again, in the instant he formed that thought, all the torches came down, the square was plunged into darkness, and Titus found himself absolutely alone in the hour before dawn.

The next day was a Saturday, so Titus had the chance to fall asleep when he slipped back into bed, and he slept late—later than he ever had before. His parents didn’t notice; they went out early to do something, and so when he woke up, muscles sore and feet raw from the dancing, head still groggy from a week of little sleep, he found he was alone in the house. He dressed slowly and then stepped out onto the front porch.

It was nearly noon. Duvbo looked exactly the same as it had every Saturday morning for as long as he could remember, but he saw it with different eyes. As old men passed walking their dogs, or mothers with their children, he wondered which ones had been with him in the dance the night before, which ones shared the secret he now possessed as well. Now every passer-by was a potential conspirator, a might-be fly-by-night reveler or story-spinner; it was as if trap doors waited around every corner and under every bush, all leading right out of reality as he had known it. Titus’s world, once no bigger than the small town from which he had pined for deliverance, now expanded around him in every direction.

When Monday found him back in mathematics class, he concentrated for the very first time on really paying attention, and fixed his eyes on Ms. Darroway’s. They were indeed the eyes of the woman who had told that dazzling story and danced that magnificent dance, though here they were somewhat tired and distant. He winked at her, as he had wanted, walking on the clouds of his new discovery, to try winking at everyone he had met since his last adventure, in case they too were in on the secret. She gave no indication she had noticed anything: either she hadn’t recognized him, or it was a secret not to be referred to outside the gatherings. Titus was comfortable with that. He would see her and their companions in surreptitious adventures later that night at the square, after everyone else was asleep.

II.

Months passed. Through a strange process of attraction, an invisible magnetism, or perhaps simply as the inevitable result of living in a town in which Nothing Ever Happened, every week brought a few more wanderers to the secret gatherings. All were absolutely astonished to discover that they were not the only ones who had harbored unspoken longings for Something To Happen, that fellow dreamers had lurked in the ranks of the polite and restrained citizens surrounding them.

The night assemblies were everything these unconfessed outsiders had dreamed of, and more—they were the very opposite of life in Duvbo: witches’ sabbats in which everything savage and beautiful, every wild impulse stifled by decorum in daily town life, was given free reign in a symphony of creativity and abandon. The conspirators juggled, walked through, and swallowed fire, erected fantastic stages and performed life-sized puppet shows, lay naked but for their masks in the moon’s rays upon the grass and composed their own constellations out of the stars in the sky. They lived for these hours, they counted down the minutes through weary mornings and tedious afternoons and uneventful evenings to the nights when they could give expression to their secret selves, when they would be possessed spirits again. As little Titus had discovered early on, no one ever spoke aloud of the meetings, or alluded to them in any gesture or sign—in fact, as it turned out, he was the only one perceptive enough to have recognized any of his fellow revelers by their daytime personas—but for all who participated, these nights dominated everything, invisibly.

And so something else was happening, in a town where no one could remember ever seeing any change at all. It was a very slight thing, something an outsider would have missed entirely and that the residents did not notice because it appeared too gradually, but all the same, it was true: an air of mystery now hung in the streets, and however placid and simple everything appeared in Duvbo, there was always something beneath the surface, like a fluttering just outside the corner of your eye. This was not all: all those sleepless nights had started to show on certain faces. In every office and classroom, in the supermarket and the synagogue and the fire department and at the post office, the watchful observer could pick out the dark circles under eyes, the drooping eyelids, the drowsy sluggishness of bodies that have not had enough rest. Nothing like this had appeared in Duvbo before, either, and so no citizen could yet articulate a question about it to himself, let alone aloud; but the scene was set.

As smart as you are, you’ve probably guessed that a tension like this could not remain unresolved forever. But there was nothing yet to light the fuse; so things continued like this for a few more months, and all that time, every week brought more people to the night gatherings.

Summer came and passed; Halloween arrived. By this time, it seemed that nearly the whole population of Duvbo was meeting at the central square at midnight. Anticipation among the conspirators was great, and preparations in the nights leading up to it had been extensive. That evening, after an early dinner, parents dressed their children up in matching plastic costumes modeled after television personalities—Titus was a cartoon character from a Saturday morning show, at his mother’s insistence—and walked them neatly around the block, collecting little sweets from the baskets that every household had dutifully provided. Then the adults hurried their children home, took the sweets from them to be rationed out one a day over the following weeks, and quickly set about the business of putting them and then themselves to bed. As soon as each one was sure the others were asleep, windows were slipped open, clothes hurriedly slipped on, and fathers, daughters, mothers, and sons slipped out into the night to assemble, disguised beyond each other’s powers of recognition, in the town square.

There the wildest, most enchanted carnival yet unfolded. Red-skinned devils, tails swinging, muscles flexing, prowled between the legs of great dragons and Trojan horses bulging with Greek soldiers; zombies and vampires and skeletons danced to rhythms beaten out on bones by ghosts; eagles flew overhead. It was as if the earth itself had opened up and revealed a fairy kingdom within; the throng stretched in every direction as far as the eye could see through the torch-dotted darkness. Although there were so many present that it appeared practically the entire populace was in attendance, each individual still felt that he or she was getting away with something that Duvbo would never and could never countenance.

In fact, if an outside observer had been there to witness the nights’ antics, and had carefully counted all the people in the crowd, the total would have come to exactly five hundred and fifty five. Who was there and who was not there were about to become very significant, though only two people knew this was coming—and they were the ones who knew least of all what was going on.

The next day Titus, like everyone else, was exhausted beyond words. In every class every body sagged, students’ and teachers’ alike. Ms. Darroway droned listlessly through her lecture, scarcely bothering to scold the students whose heads lolled on their shoulders and chests. After school, the boy practically staggered home—to find something new and unexpected had, once again, taken place.

These days, he only checked the mail out of habit, in unthinking faithfulness to a routine he no longer regarded with any serious optimism—his longings for adventure and escape were fulfilled by the nights’ activities, anyway. But there, just dropped off by the drowsy mail woman, was a letter unlike any other that had ever arrived on his doorstep. It wasn’t a bill, and it wasn’t an advertisement, either, as far as Titus could tell. It seemed to be an announcement: it was a single sheet of thick paper, folded in half and taped shut, with ominous lettering on the front that read simply FELLOW CITIZENS OF DUVBO. In an instant Titus was awake again, nearly bursting with curiosity. This was the first unexpected thing that had ever appeared during daylight hours—could it be that the secret world was about to erupt into being around the clock? As curious as he was, he knew the daytime rules still applied, and they dictated that he wait to find out what this message might be until his parents came home and opened it themselves.

It seemed an eternity before his mother and father were both home from work, and then Titus had to wait all the way through the usual silent proceedings of dinner. Finally, when the boy was at his wits’ end, his father drew out the mail to go through the dismal daily process of paying bills and balancing accounts. He dealt with every bill at length, reading every invoice and receipt twice and perusing all the fine print with a magnifying glass to be sure not to miss anything, making notes on his clipboard as he went, before he came to the announcement. Titus held his breath. “Oh, you open it, honey,” his father sighed, passing it to the boy’s mother: “it’s nothing important.”

She did, and peered at it for some time, until Titus could restrain himself no longer. “What does it say, mom?” he ventured, trying to sound nonchalant.

“It’s some of kind of public notice, I think,” said his puzzled mother. “It requests our attendance at a meeting tonight of ‘All Concerned Citizens of Duvbo,’ at the town council building. It doesn’t say much more than that.”

His father grumbled about always having to go to meetings and how the last thing he needed was another one but he figured they had better go anyway since you can’t risk looking bad in the eyes of the community, and all the same what a chore it all was, wasn’t it. “Can I come, too?” queried Titus, in his most courteous voice.

“I don’t think this is the sort of thing for young boys like you,” she answered definitively, and that was the end of the matter. So of course, well-practiced prowler that he was by now, Titus sneaked out and followed his parents at a careful distance when they left an hour later to attend the meeting.

The town council building was one of the oldest in Duvbo, and correspondingly dour and stuffy, like a bitter old man clinging too tightly to tradition. Inside, the adults sat stiffly in rows of uncomfortable chairs, backs straight and aching, hands folded in their laps, in much the same way that a decade and a half of schooling had taught each of them to when they were younger. Virtually every grown person in the town was there: the firefighters were seated near the front, Titus’s mail deliverer just behind them, and in the center were all nine teachers, including Ms. Darroway—taciturn as she was in class, and still wearing the same grey dress. There was a dry, awkward silence in the room, broken occasionally by the hiss of a nervous whisper, or the screech of a moving chair as an embarrassed man arrived late. Hidden in a bush to escape detection, Titus looked on through a window from outside.

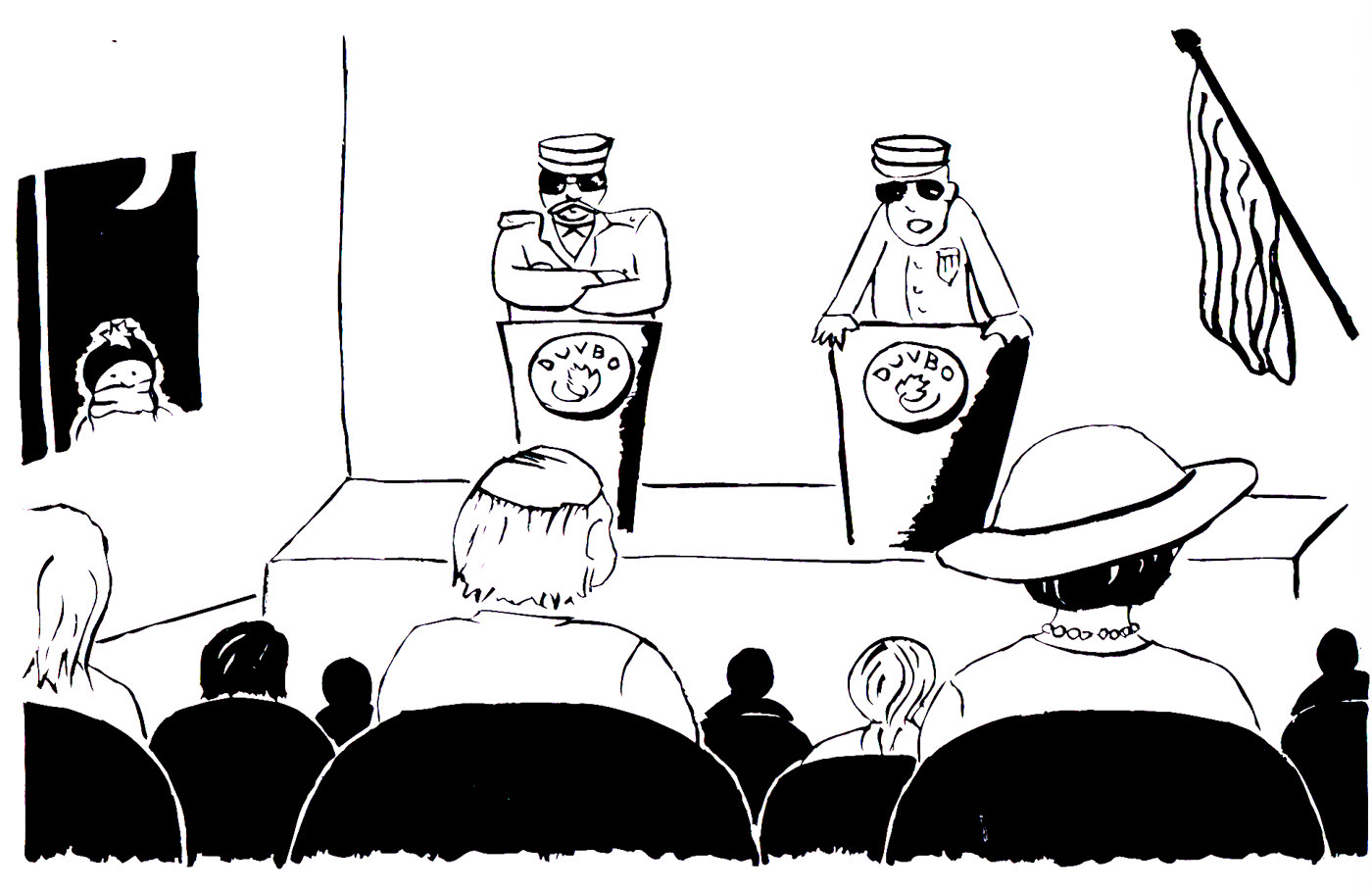

At precisely eight o’clock, two stern, grim middle-aged men stood up from their chairs and advanced to the podium in the front of the room. One of them took his place at it while the other stood behind him, casting vaguely menacing and judgmental looks around the audience at random.

“It has come to our attention,” began the first of the two retired army officers, for that of course was who these men were, as you may remember from the beginning of the story, “from certain sources we need not divulge, that Duvbo has become a fallen town, a den of iniquity, a place where evil has taken hold. We have summoned you to this meeting because, as you well know, it is your duty as Responsible Citizens to root out all blemishes and stains, all Unacceptable Behavior, from the precious soil of our community, and steps must be taken immediately to do this before our beloved heritage of Honor and Morality is lost forever.”

The second man stepped to the podium and replaced the first, and the first in turn took on his role of glaring at the audience. “Back in our day, in the Service, we ran a tight ship, as they say, so I believe you’ll all agree when I say that we are the right men for the task of cleaning up Duvbo. What you must do is report to us any inconsistencies, any foul Deviations you are aware of, beginning tonight, at this moment. Well then, who’s first?”—and he joined the other in glaring.

Titus craned his neck to see the faces of the adults throughout the room. They were all casting furtive glances about, guilt writ large on every face, each practically wondering aloud who the wrongdoers were but secretly cringing lest his own culpability be uncovered. Months of living in secret had subtly, inexorably bred into all of them the sense that they had something to hide, and now that the question of evil had been broached, those feelings rose to the surface. Every citizen felt the officers must be talking about him, and looked around to see what he could expect if they were. Who could be trusted here? Who was a part of their secret intrigue, and who was a spy waiting to catch them in it? Could fellow conspirators even be trusted, now that the pressure was on? None of them had needed to consider such questions before. The officers might have been bluffing, might have been referring to a boy who had copied his friend’s homework or a driver who had run a stop sign; but the reception of their claims—as if everyone knew exactly what they were asking about—was so suspicious that now there was no going back. No one spoke, or even dared cough; the tension became unbearable. Finally the mayor came hesitantly forward.

“Good men,” he began, deferentially, “of course we are all very honored as well as outstandingly fortunate to have you put your services at our disposal to expose and eliminate this—er, contagion—in our midst. I move that each citizen goes home to make a full report of all the suspicious activities and criminal behavior he is aware of, so when we reconvene in a week to address this matter further, we will have some reference material for, uh, reference in pursuing this matter, arhum, further.” He straightened his tie, twice, and attempted to compose his face into an ingratiating expression while maintaining the dignity befitting a dignitary.

“All right then,” growled the second army officer, with a look that snarled Consider Yourselves Lucky, “we’ll meet again in a week, and you’d all better have some evidence by then of what’s going on and who’s to blame. Remember, citizens,” he thundered in a concluding tone that made Titus’s skin crawl, “in the war of good against evil, right against wrong, tradition against corruption, you are either one of us, or you are against us. There is no middle ground to muddle around in. See you in a week, with your reports, and God Bless You all. Oh, and policemen—” he snapped, singling them out, “keep your eyes especially open this week. This is supposed to be your department.” He turned, and, with his fellow ex-officer behind, stomped out the door.

Every citizen of Duvbo woke up the next day feeling hunted, guilty. The time-engrained habits of concealment, the exhaustion that attended such double lives, these now felt like bodily indictments—if they had nothing to be ashamed of, why had they been hiding? And if what they were doing was healthy and right, why were they exhausted all the time? Forced now to assess their nighttime activities by daytime standards, they found they could not translate between the two contexts, could not justify themselves. Each felt he could never explain what he had been doing to those who had not been a part of it; in the meeting room of the town council building, with those two men glaring at them, some had even wondered if they were indeed monsters in disguise, if their nightly pursuits proved they were in fact evil. So while it might seem surprising to an outsider that the citizens of this little town could so easily be turned against themselves and one another, it was not actually so unusual, after all.

For the following week, daytime Duvbo crackled with rumors and suspicion. Everyone went about with a great show of righteous outrage at the discovery of possible illicit influences in their precious community, and gossip abounded as to who might be responsible. All mature citizens were too well-mannered to refer to anyone by name, but insinuations proliferated: the residents of each street spoke of other streets, “bad neighborhoods,” just as the employees at each company spoke of the bad sorts that might be found in less honest lines of work, just as, at the end of the day, husbands and wives spoke in hushed tones of the bad influences of other families. Everyone was anxious, above all, to direct attention away from themselves, since each person was sure that, were their own nocturnal activities to come to light, their fellow citizens would give no quarter in the rush to attribute guilt and deflect suspicion.

By night, the gatherings still took place, but in decreased numbers, and there was a tension in the air that had never been there before. In denial about the measures being taken in the daylight world, afraid to speak aloud about the situation but unable to shake the burden from their minds, the conspirators who did show up threw themselves all the harder into their invented ceremonies and flights of fancy, but to less and less avail: a dark cloud hung over every moment of abandon, every step of each dance. At least here, in open if anonymous admission of their guilt, people did not look at each other with hostile or judgmental eyes; but each morning as they passed their fellow citizens on the street, things were decidedly different. When once they had looked on passers-by, like Titus did that Saturday morning, with a sense of joy and companionship, wondering if they too were secret revelers, they now regarded all others with fear, lest they be judges waiting to pass sentence upon them, or former comrades who would turn them in to save their own skins.

At the next town meeting, every adult arrived with a complete report. Some brought big sheaves of papers under their arms, others great folders divided into sections according to arbitrary systems of categorization, others thick notebooks with every possible infraction of public morals and tastes that had come to their attention noted and annotated. They sat, heavy testimonials in their laps, backs ramrod straight, lips tight, faces blank masks, looking neither to the left nor the right, and waited for the proceedings to begin. No one was late this time, and at the appointed hour, the mayor, anxious to maintain the image of responsible authority, arose to officiate. From their seats at the front of the room, the two ex-officers regarded him with expressions of acid impatience; Titus, too, looked on from his post in the bush.

“Fellow concerned citizens,” the mayor began, and cleared his throat as if to command attention, in a room already empty of all distractions: “we are gathered here to show our concern about, our commitment to, our deep-seated feelings for the continuity of our proud tradition of greatness and purity in this town which we all so know and love, the name of which you know as well as I, fair Duvbo. I hope you’ll join me in these trying times in holding out a light of hope to the future—“ and he went on, and on, and on in this style for some time, before one of the ex-officers cut in and demanded he get down to business.

The mayor summoned the first citizen to the podium to make her report—the roster was arranged in alphabetical order, so it was Anna Abelard, the retired grocer. She shuffled through a veritable mountain of loose papers, and approached the stand with her eyes on the floor. Anna had a gentle heart, and much as she knew what was expected of her, she hadn’t been able to bring herself to specify any names or risk endangering anyone else, so her entire account was a string of abstractions and ambiguous references to unspecified people and events. For the purposes of the ex-officers’ inquisition, it was absolutely useless, but they let her stumble through it for a good half hour, presumably because they could tell this was even more mortifying for her than it was exasperating for them. Time seemed to grind to an even slower pace than it kept in mathematics class.

Then without warning, without asking permission, someone stood up from the audience. It was Ms. Darroway. Her face was lined with years of little sleep, the dark circles under her eyes were heavier than ever, but the air of elderly irritation she affected during the day dropped away and her bearing here was suddenly as imposing as it was when she presided over storytelling circles in the witching hour. “This is foolishness, and you know it,” she stated plainly. “Let Anna be—she obviously doesn’t have anything to tell you. If you’re so certain there is wickedness in our town now, why don’t you tell us where it is?”

Both former military men shot to their feet in indignation. “Hold your tongue, schoolteacher!” shouted the first. “This is an important meeting, not to be interrupted by idle questions! You should know from your own profession better than to talk out of turn!”

“So tell us where it is,” she insisted, calmly.

“I’ll tell you where it is,” yelled the other, “it’s in teachers like you who set bad examples! How are our children supposed to grow up with a proper respect for rules and authority with women like you for role models?” He stepped back to address the audience in general. “And it’s in all of you who let the moral fabric of this town fray and unravel! It’s written on every face in this room, the secrecy in your movements, those mysterious bloodshot eyes, the indifference you show to important matters like this! We may not know what’s going on yet, but mark our words—we’ll find out!” He stomped out of the room in a rage, his henchman close behind.

At the mention of bloodshot eyes, everyone in the room had flinched despite themselves. They looked around, and it was true: on practically every face was this sign of guilt, the evidence of a double life. So the game was almost up: the two self-appointed detectives knew nothing yet, but they knew where to start looking, and it was only a matter of time before they would uncover the truth about Duvbo. The townsfolk trembled, gazing at one other in fear—for however many of them were involved, it only put each one at greater risk if they could not trust each other—and hurriedly began filing out the door to head home. Only the mayor remained behind, wringing his hands at the scene his citizens had caused and yearning for the simpler days when his greatest concern had been which tie to wear for the Christmas parade.

That night, five hundred and fifty five conspirators sneaked out their bedroom windows, one by one, each going to greater pains than ever not to wake the others from their sleep. They crept through dark streets thick with the shadows of their sisters, brothers, fathers, mothers, neighbors, and coworkers, doing everything to avoid detection until they arrived, in disguise, at the main square. Here, a great bonfire burned, and Ms. Darroway, clad in her magnificent bearskin, was already leading a discussion of what was to be done.

Tensions were high and accusations flew. Some held that the gatherings had to be suspended until a safer time; others, speaking eloquently of the freedom and energy they prized in these moments, believed they could continue to take place, but at more prudent intervals; still others argued that it was foolish and irresponsible to think of gathering this way ever again, that it endangered everyone too much. All agreed, if nothing else, that the good old days had come to a close, and dark times descended in their stead.

“But what are we supposed to do, if we can’t come together here anymore?” demanded an impassioned young woman no one recognized as a local real estate agent, clad in a scintillating dress of green sequins and wild feathers. “All of us went wandering and discovered this midnight carnival because life without it was too vacant to bear! We can’t simply go back to those barren lives, can we? I almost feel as if I’d rather die!”

“I wish I could tell you there was another choice, dearie!” said Anna, the retired grocer, sadly, from behind her silver veil. “But I think we have to let it go. That’s the way life is. There was a life for me before I found my way here, you know, and there will be a life after, for all of us, though it may not be what we’d prefer.”

“We don’t have to let it go unless we choose to,” countered Ms. Darroway, hotly. “We decide what risks are worth taking, we decide what we give up and what we keep. That’s how we made this secret society for ourselves, and if we suspend or dissolve it, it should only be because we believe in doing so, not because we think we are the victims of fate. Make your decision for yourself.”

“That’s easy for you to say, perhaps!” It was Titus’s father. Titus himself looked on, his face concealed as usual by his trusty scarf, in unnoticed mortification. “Some of us have children. We have to think about their future, about making this a healthy environment for young people! We’re not at liberty like you must be to make decisions for ourselves alone. In fact, when you make your decisions, they affect the rest of us as well! What if you and people like you keep coming out here, causing trouble for all of us? How are we supposed to raise our children in a town where things like this go on?”

Little Titus wanted to demand how children like himself were supposed to grow up in a world without magic, without dances and costumes and fairytales, but he was afraid to speak up, afraid too of being recognized by his parents. “You’d have us give up our lives all over again!” shouted an angry figure from the shadows, a fireman by day. “What did you start coming here for, anyway?”

“Who are you to risk our lives for us, and our children’s lives?” retorted another enraged parent, and real quarrelling broke out. Everyone tried to shout louder than everyone else, and for many minutes the chaos spiraled out of control—until a sudden realization choked the words in every throat: the townsfolk had lost track of time and dawn was already breaking. In a panic, they scattered everywhere, leaving the square in such a hurry that they forgot the care they had always taken before not to leave any evidence of their gatherings.

The next morning, while doing his rounds, one of the policemen came upon the still-smoldering remains of the fire in the center of the town square. He tried to pass it nonchalantly, stifling a shiver of fear as he realized how careless he and the others had been, but then he caught sight of another citizen at the far end of the street. If he was caught deliberately ignoring such obvious evidence of unusual activity, it would be taken as a sign of complicity; he put his whistle between his teeth and sounded the alarm.

The report of his finding spread like wildfire, and the responding outcry was immediate and intense. Word passed from mouth to ear to mouth around the town in a matter of hours, and an emergency meeting of All Concerned Citizens of Duvbo was called for that evening. All afternoon speculations circulated as to what outlaws or fiends might have been doing in the very heart of Duvbo the night before, and how they could be captured and brought to justice; everyone fought to outdo each other in shows of righteous indignation.

This time the mayor did not even make a show of administering the meeting. The two former officers had set themselves up at a tall table in the front, from which they glowered at everyone else as they filed in. This was the tensest atmosphere yet: hostility hung in the air like an electric charge, and while no one dared make eye contact with anyone else, condemning glances were cast like darts all around the room.

“As spokesperson for the emergency panel that has been established to handle this situation, I call this meeting to order,” began the first ex-officer. “Obviously you are all well aware now of how real the threat we warned you of is, so I trust we will not have to bear any more interruptions tonight”—he cast a withering look at Ms. Darroway—“and will be free to get down to the business of cleaning up this town.”

“Clearly, the undesirable elements, the subverters, are meeting by night, plotting heaven knows what sickening disgraces and crimes,” continued the other man at the table. “Police chief—”

“Yes sir,” responded the haggard-eyed chief of police.

“You’ll need to extend your patrols to cover every hour of the night in addition to the standard daytime schedule, starting this evening, so the monsters can be brought to justice and their plans foiled.”

There was a long, uncomfortable pause. “I’m afraid I can’t do that, sir,” responded the police chief, and one of his men nodded. “My men will need at least one good night’s sleep to be ready for a shift change like that. We can get the patrols in effect by tomorrow night, but that’s the soonest. I’m sorry.”

“Well, lock your doors tonight then, fellow citizens!” roared the first ex-officer, and it sounded more like a threat than a warning. “This will be the last night any funny business takes place in this town! And tomorrow we’ll meet here, at the same time, to discuss some other Big Changes that are going to be made around this place.”

After midnight, only the bravest few dared to congregate for a final time. Ms. Darroway was there, and the woman who delivered the mail to Titus’ house, and the young lady in the green sequins, as well as a few others, including the police chief who had bought them one more night to bid a melancholy farewell to each other and the world they had created. Titus was there, too, of course; his parents had indeed locked and barred the doors of his house, but they hadn’t thought yet to do the same with the windows. Spirits were lower there at that moment than they had ever been before in Duvbo, day or night. No one spoke; they simply sat in a circle around the small, struggling fire, staring into its dwindling flames, lost in their own thoughts.

Finally the woman in green broke the silence. “It’s just so sad, so unendurably sad,” she began, haltingly, “to discover what you spent your whole life longing for, to find that it was within you all along, and to explore it, to find out how much bigger and wilder it is than you’d ever imagined, and even share it with others, only to lose it, all of it, because of their fears.”

“Because of our fears,” the sorrowful police chief broke in. “Because of our fears. And there’s nothing we can do, however much we want it, however much it breaks our hearts.”

Ms. Darroway, still tall and proud even in this bleak moment, remained silent. Titus looked at her in horror and dismay: it was unthinkable to him that this powerful woman, who was practically a supernatural being in his eyes, might become, again, a mere math teacher, a woman who had to lecture and reprimand indifferent students all day as an actual life’s work rather than an alibi. Just as he had once before, on the first night he ventured outside his neighborhood, he gathered his courage—and spoke up.

“Is there really nothing we can do?” demanded the boy. “Aren’t we giving up too easily? Are you sure there isn’t something we haven’t thought of yet?”

“But what could that be?” asked his mailwoman, who still didn’t know that he had once believed so fervently that she could bring him an invitation to another world.

“Well, let’s think!” Titus furrowed his young brow. “if this is our last night together, and tomorrow we will never be able to meet again, well, at least we are free and together now. That’s something.”

“Yes, go on,” encouraged Ms. Darroway, quietly. “What can we do with that?”

“If we’re still free now, and we don’t want to lose that, and we know we’ll lose it tomorrow”—Titus pondered this, but there seemed no other way around it—“then I guess the only hope for us is that tomorrow doesn’t come.”

“And that’s impossible,” said the policeman. “The sun will rise in just a few hours, and then I’ll be just a policeman, nothing more, for the rest of my life.”

Titus was much younger than the others, though, and not as resigned to the inevitable as they were. “Who says it’s impossible?” he replied, surprised at his own voice. “I believed that it was impossible that you could be anything more than a policeman, before I stumbled into the dance here that first night. All we need is some magic to stop the sun from rising, and this world will be ours forever, as it has been only for a few hours at a time until now.”

“Magic? Yes, that’s what we’d need,” sighed the woman in green. “It’s too bad it’s only in our stories. We could use it in real life tonight!”

“Maybe we can!” said Titus, standing up. “What we need is a magical dance, a ceremony to stop the sun. Will you join me in making one?”

The others were silent; the hope in the little boy’s voice only saddened them more. But finally Ms. Darroway spoke up. “It’s true that when I came upon my first night gathering in Duvbo, years ago, when there were fewer people meeting than we are here tonight, I felt as though I’d found something magical,” she began. “It was like a miracle, something so totally different from everything I’d known that it seemed to defy the very laws of nature. If that’s what we’d need to discover again, tonight, for this story to have a happy ending, perhaps we shouldn’t despair yet, since it has already happened to each of us once.” She looked around at the others, her eyes bright in the firelight. “I’m ready to dance with the young man, unless any of you have a better idea. Even if it is our last night here, it’s better we spend in on our feet than at our own funeral.”

The others slowly rose and joined Titus on their feet. Titus seized a great burning branch from the fire, and lifted it high over his head, waving it defiantly towards the east. Ms. Darroway did the same, and the others followed. One of the firemen began to beat out a quiet rhythm on the one drum that remained with them, and the dancers began stamping their left feet, then their right. Titus took the towering woman’s hand, and they began spinning.

As they had so many times before, they left the world of solid things and gravity, and entered the world of energy and motion. The stars in the night sky, the red glow of firelight on the trees, the grass and shadows underfoot became a blurred background against which their bodies sailed, crisscrossed by the streaks of white light their torches left in the air. The rhythm intensified and accelerated. Their feet were flying over the soil, barely touching down long enough to push off again, their hearts pounded with the drums—their hearts were like drums themselves, inside them, urging them on. The others too were whirling now, coming in and out of their vision like comets, trailed by the afterimages of their torches, wild animals set free for a moment from fear and inertia and weight itself.

But they knew they had to break out of everything, to leave the world they had known entirely, so they danced harder and faster. Harder, so the drummer feared his thumbs might fly off; faster, so dizziness welled up in them in almost unendurable waves; harder, so they thought their bones would break and their fingers snap away; faster, until it seemed that their feet and hands and muscles themselves were fire, that they danced as only fire can dance through burning leaves. They danced as though mad, as though animated by demons or angels; leaping into flight, they kicked against the ground so hard it seemed the force must stop the earth’s rotation, must halt it dead in space.

They were so caught up in their dance, so absolutely possessed and entranced, that they didn’t even notice the light creeping into the sky in the east. They didn’t notice the first bird calls, as the breeze lifted the branches of the trees overhead; they didn’t notice the red clouds burning away to reveal the first ray of sunlight shining over the horizon; they didn’t even notice as the sun crept up, over the hills, and morning began. There they spun and flew and twirled, the torches shooting out sparks around them, sweat raining down upon the grass from their bodies, eyes rolled back in their heads; they were oblivious to all but the magical world of the dance. This is how their fellow townspeople found them that morning.

And a strange thing happened. As the first early risers filtered out into the streets, and saw their companions from previous nights of abandon here in the sunlight, leaping without shame in the same unchained motion they too had savored, one by one they came forward and joined them. They, too, began to dance as if it were still night, as if they were wearing masks that hid their identities, as if no one were watching—as if it were the most natural thing in the world. Slowly all Duvbo assembled in that square, as they had so many midnights before, but now with no camouflage or subterfuge; all, that is, of course, except the two retired army officers, who had the sense to get out of town immediately and never come back.

The schools and offices were empty that day, and the next day as well; and no one in Duvbo ever had to sit up straight and quiet, or struggle silently with boredom, or cast a suspicious eye on a neighbor again. Some say you can still find the townspeople there, that life in that village is a continuous festival that knows no beginning or end; others say Duvbo is a hidden and wandering town, that it appears for moments or hours in every city across the world, unexpected and unpredictable, and one day it will emerge everywhere at once. Still others insist that the whole thing is just a myth, or a bedtime story to be told to little children without being believed; but at your wise age, little one, I’m sure you know better than to believe the ones who speak like that.

…like all children are born to smuggle in the end of the world with no one qualified to herd them…